SOTA Spring 2024 Trans-Atlantic Summit to Summit Event

April 20th, 2024

Most of these photos have captions, but I cannot figure out how to get this WordPress theme to actually display them. I miss the straightforwardness of Drupal. /s

This past Saturday was the spring Trans-Atlantic Summit To Summit (TAS2S) event for Summits on the Air (SOTA). It occurs twice annually, the other event being in November. I did that one as well and had a lot of fun, but it’s too far gone in my hazy memory to do it justice in a blog post.

For those reading this who aren’t fellow hams, Summits on the Air is a… game(?)… activity(?)… where amateur radio operators will climb to the summit of a hill or mountain and try to have as many people contact them as possible. One can win awards for various things, including making contact with another radio operator on another summit somewhere locally, or even somewhere else in the world. Participating in this is the reason I originally got into ham radio, as it weirdly scratches the same itches that geologic mapping did back when I was employed doing that. Being out in the woods without a purpose is very important and can be transcendent, but being out in the woods with a goal, utilizing expertise and art and skill, equipment, recording data, combining science and practice, etc., is very satisfying. Plus, since the bulk of my outdoor time for the past 10 years, both professionally and recreationally, has been unintentionally solitary, it makes being outside a little less lonely.

This event is special because lots of radio operators, on both sides of the Atlantic, are on mountains all at the same time, all trying to contact each other. There’s a special and fun United Colors of Benetton nerdy fraternity in that; to take part in a concrete activity, globally at that, that’s bigger than ourselves and that’s happening purely for the joy of it. Ot has a somewhat similar feel to the eclipse earlier this month. To paraphrase discussions had among fellow hams on Mastodon, we’re all little fireflies out there in the darkness, sitting on our mountaintops, trying to see everyone else’s reflections bouncing off the ionosphere. Since, in my life, most of the things I pay attention to, and participate in, globally, focus on much less fun and downright scary topics, this simple act of intellectual curiosity, fellowship, and outright nerdery… in short, being human… with folks in other countries, on other continents, to spite all that is a welcome reprieve and a reminder of what so many of us are fighting for.

So, for Saturday, I decided to activate Mt. Massamet / Bald Mountain (W1/MB-017). At 1591 feet (485 m) it looms over the quaint and increasingly tourist-oriented yet quaint village of Shelburne Falls, former home of the ostensible oldest cutlery manufacturer in the world: the Lamson & Goodnow Cutlery Factory (now artist studios and a bookstore). I wanted a short drive this morning, with a relatively quick and easy hike to the top: the European radio operators also participating in this event had a 4+ hour head start on the eastern U.S. I wanted to catch them while they still had daylight on their respective summits and radio propagation paths on the higher HF frequencies between the eastern U.S. and Europe, over the Arctic (a gentle reminder that we live on a sphere), were ostensibly still open, since the ionosphere favors the morning for such magic to happen between the two.

One can hike up the mountain from town. But that approach is very steep: a 1200 foot (366 m) climb in the 2 miles (3.22 km) from the Deerfield River below. Being very out of shape due to AI issues this past year, I opted to drive to a trailhead on the backside of the hill to do a climb of only 300 feet (91.5 m) over 1.2 miles (1.93 km), starting from a higher elevation on the mini-massif of which the Mountain forms the western flank, part of which is locally known as The Patten District: a highland bounded on the west and south by the North and Deerfield Rivers, and the east by gorge of the Green river and the western escarpment of the Connecticut Rift Valley. The British Empire chose this highland as the location of two forts (Lucas and Morris) during its mid-18th century incursions (known now as the King George’s War) into the sovereign lands of the Mohican, Pocumtuc, Nipmuc, and other kin of the Wabanaki Confederacy. It’s a shorter and gentler hike given the 20 pounds (9 kg) of radio gear and water I was carrying on my back.

When describing the mountains here, we get into the complications of describing the topography of my part of the Northern Appalachians. Western New England, including the Berkshires in Connecticut and Massachusetts, and the Green Mountains in Vermont, and even the highlands of central Massachusetts and southern New Hampshire, on a regional scale, are less mountains and more erosional remnants of a high plateau cut by relatively deep and steep river valleys and gorges. In these parts, the mountain-building portion of the very long-lived Appalachian orogeny had ended about 280 million years ago: the landscape had mostly been eroded nearly flat into a peneplain since that time. But in the Miocene epoch of geologic time (starting ~23 million years ago and ending ~5 million years ago), the eastern part of the continent got uplifted again into a high plateau, establishing and entrenching the river and stream networks, valleys and gorges, etc. we see today. This topography was later enhanced, starting a vanishing 20,000 years ago, by the melting of a miles-thick sheet glacial ice that had covered the northern half of the continent — river gorges steepened and carved anew by the unimaginable amounts of water draining off that ice in the summers + the land rising again, and quickly, once the weight of that ice stopped pushing it towards the Earth’s mantle like a toy boat in a bathtub (humans were indeed around on this continent to witness that entire process and recorded it in their histories). The more prominent summits here (and coincidentally, most of the SOTA peaks in the region) are the erosionally enlarged remnants of what were once much smaller hills mountains that existed prior to that Miocene peneplain: the valleys around them being made deeper made those hills into mountains. The much bigger White Mountains and the Adirondacks, though, are a bit more complicated story for a another time.

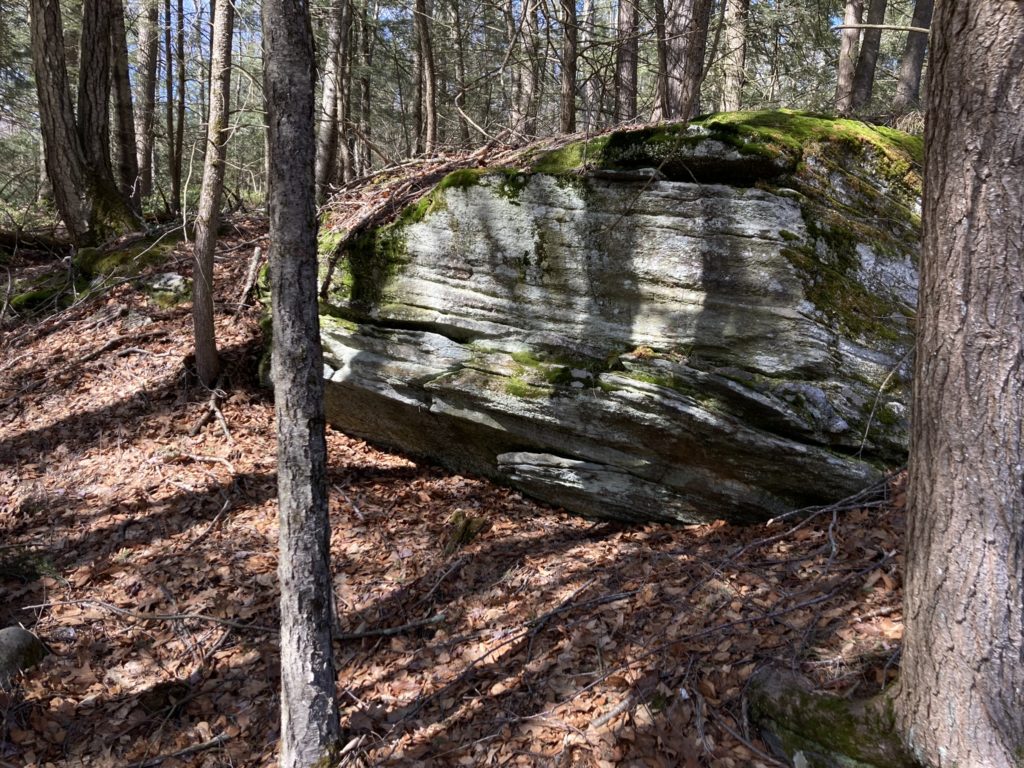

The morning started off with the last dregs of light rain that had moved in overnight, with a low stratus cloud ceiling hanging over the region and undercast of mist in the river valleys. Even though the temperature was only about 50 F (10 C) the high dewpoint made for a sticky hike. I started along the woods road that goes through the Mass Audubon High Ledges Sanctuary. The road eventually leads to a popular series of rock ledges with a nice western view up the Deerfield River Valley towards Mt. Greylock, but that was not my destination today. About halfway along the road, in an old apple orchard and meadow with blown over tall grass abd brambles, I turned south on a smaller public trail leading through privately owned land and, hemlocks, hardwood, and silver birch forest, to the summit. The trail got soggy in places as it skirted small high-elevation woodland-wetlands that are a unique and wonderful feature of western New England. It was fun to see the mottled leaves of trout lillies poking through the leaf litter, and abundant fungus and lichen swelling with moisture on fallen trees blocking the trail. Passing ledges and pavements of the turbiditic schists of the Early Devonian Goshen / Waits River Formations that border one of these small boggy areas, I was startled by the explosive lawnmower-start buzz of a grouse I had unintentionally flushed. The monkey-calls of a pileated woodpecker sounded in the distance: all good sounds that I have missed for living in the village. As I gained elevation, the large cell tower that serves our part of the Deerfield River Valley came into view, along with a loud peel of metallic clangs as some sort of woodpecker hammering away at some resonant portion of the tower, marking territory. The trail rejoined a woods road leading upward, and, continuing the gentle climb along it, the stone fire tower at the summit suddenly came into view.

The firetower, built in 1909 and put into service in 1911, is supposedly the oldest continually active fire lookout in Massachusetts, with some speculation about it being the oldest in the U.S. (which I doubt). Stone fire towers are a rarity in this region: we have many firetowers (and more forest fires than people might think), and most of them are built of steel. The stone for the tower was ostensibly quarried on site, though local LiDAR data doesn’t show any evidence of a bedrock quarry anywhere near the summit. My geologist eye notes the stone itself is granite and granodiorite: not consistent with the sheared looking amphibolites of the Cambro-Ordivician Collinsville Formation at the summit, which underlies the Goshen / Waits River Formation here.

Geologically, the bedrock from which Massamet Mountain is carved lies at the eastern edge of a large structure in the Earth’s crust we call the Shelburne Falls Dome. This dome structure is independent of the topography and isn’t defined by it: it’s older… much older… arguably an eldritch Elder God (although the core of the dome seems to correspond with the bowl shape of the Deerfield River valley here). If we imagine the Earth’s crust as wood, with the grain of the wood representing the grain of the rock and flat-lying strata (not entirely accurate in this case, but fellow geologists, cut me some slack here), domes are kind of like burls in the wood grain on a board that has been planed flat: an upward warping of rock layers where older rocks are exposed in the center of a bullseye of younger rocks lying on top of them. On a geologic map, looking down from an imaginary point in the sky, these features indeed resemble a bulls-eye, or a knot in a wooden board. The Appalachians have dozens of these domes in the Piedmont, Blue Ridge, and similar rocks up and down its length, although the Piedmont and Blue Ridge, as topographic features in New England, aren’t really present: because glaciers. I walked through the tilted layers on the edge of this dome as I hiked west and then south up to the summit, passing outcrops of the younger Goshen / Waits River Formations at lower elevations on the dome’s east flank, and then stepping over pavements of the older Collinsville Formation at the summit as I hiked west and south into the dome’s core. The dome structure itself, deforming the layers and fabrics of those rocks, which are older than it, was created in stages about 380 to 280 million years ago by tectonic forces (that’s a very complicated story spanning several scientific papers) at the height of Appalachian Mountain building during the assembly of the supercontinent Pangea, after the closing of the Iapetus ocean. The Goshen and Waits River Formations are metamorphosed sediments that formed on the continental slopes of small basins on the edge that ocean, between the larger proto Turtle Island (North American) continent (what geologist call Laurentia) and micro continents further out towards the ocean. Our continent was on its side and at the equator back then, and the whole situation looked very much like southeast Asia / Oceania does today. The Collinsville Formation, however, is a very different beast. It’s older, about 480 million years or more (I forget the latest geochronology on it and don’t feel like looking it up), and is very sheered out solidified magmas that were forming under the Earth’s crust during the start of the Appalachian Orogenic Cycle during the Taconic orogeny.

But this is a ham radio blog, and I digress…

Putting my pack down, I customarily climbed up the inside of the tower to see the view out of the tiny windows near the top. The tight spiral staircase inside gives big Elder Scrolls vibes, although there were no torches to light the darker parts and, much to my disappointment, no draugr deathlords waiting at the top guarding a chest full of loot. The views were mostly clouded in, although I could see the village below through breaks in a lower cloud layer that was hanging out in the valley.

Returning to my pack, I chose a spot a little ways from the clearing at the summit, knowing that as the day wore on hikers would be visiting the tower. Taller trees with an open understory were at this spot, making it easier to deploy my antenna.

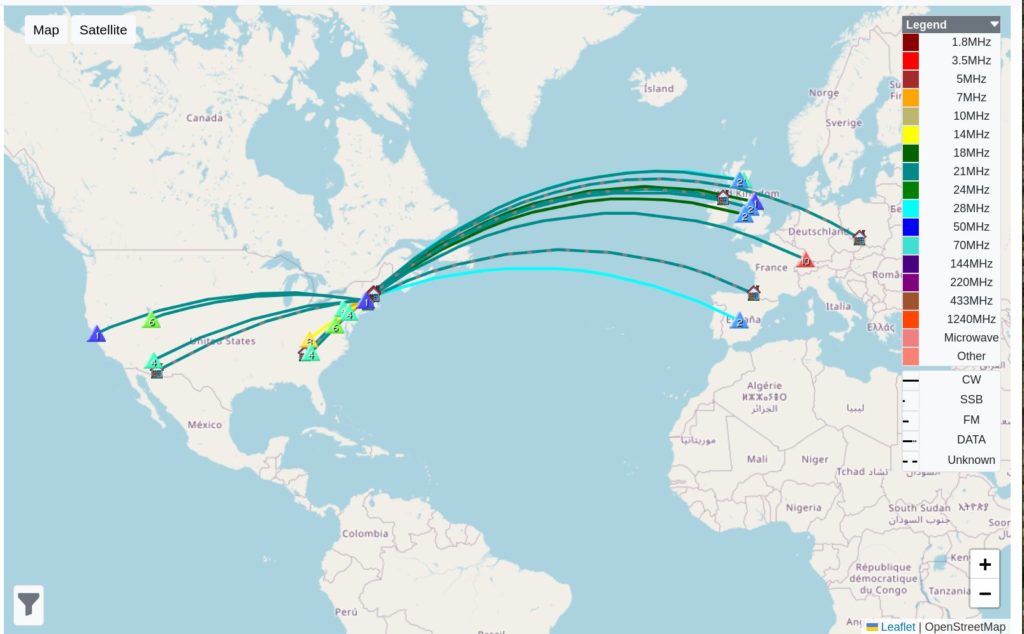

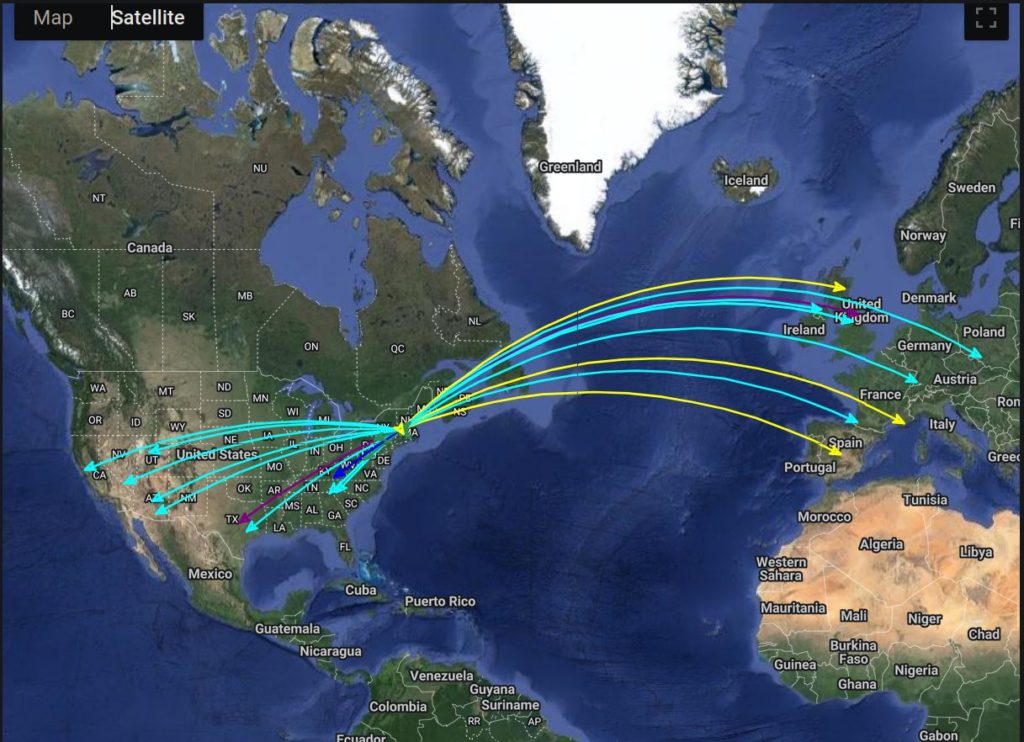

I had stayed up late the night before making a Norcal Doublet, or, more accurately, a 44 ft open-wire fed doublet (of KR5V design) to test out on this activation. After deploying the antenna in an inverted V, oriented at 330 degrees lengthwise (intended to be 315) to be high gain at Europe, and, more importantly, having a snack, I sat myself down on a mossy rock and went to work trying to chase European SOTA activators listed on SOTAWatch. I was quickly disappointed: the bands were in horrible condition. I wasn’t really hearing anyone, and what few activators I could here were down in the static and barely intelligible, with really bad QSB. I decided to try my luck and start calling CQ on the 10m band of frequencies, and was immediately rewarded with a local contact in NH, about 95 miles away: wonderful, but not my fellow European folks on top of summits that I was looking for.

After getting no responses after that for quite a few minutes, I switched to the 17m band, as 12m and 15m were even more dead than 10m. I was, again, immediately rewarded with another New Hampshire contact, 94 miles away, near the previous QSO. Just a minute later, however, I got my first trans-Atlantic summit-to-summit (S2S), from MW0IDX on top of Foel Fenlli in Denbighshire, Wales, followed by a station in Texas. After a few more minutes with no answer and the G-90s waterfall and being devoid of signals, I switched to 15m. And, as luck would have it, the band had opened up! The chickadees high in the tree canopy chose this moment to start up their springtime calls, which, for the longest time, I thought were phoebes as that’s what it sounds like they’re saying to my ears: “Phoeeeeee-bee. Phoeeeee-bee.”. QSOs now trickled in with chasers in Arizona, Poland, Georgia, with S2S’s from WW4D on top of Sassafrass Mountain at the very western tip of North Carolina, and another trans-Atlantic S2S with M4ZCB and M1MAJ on top of Boulsworth Hill – Lad Law in Lancashire.

Calling CQ was going slower than I liked, so I re-checked my antenna orientation again: it turns out I was 15˚ off and it was oriented 330˚ (30˚ west of north), placing its lobe of highest gain more towards eastern Europe and Russia where it was already dark, and propagation on the higher bands was likely fading out. While it likely didn’t make much difference, I re-oriented the legs to be in line with 315˚ of azimuth so the highest gain of the antenna would be pointed at the British Isles and northern Europe, where I knew the most activators on summits were likely to be. I then set down to chasing other folks participating in the event across the bands, and succeeded in contacting quite a few European activators still on their summits! Ionospheric conditions had indeed improved. But the deer and dog ticks had finally found me, and I was now picking the off my pant legs, arms, and back of neck throughout the rest of the activation. In my own experience, this time of year is the worst for ticks as things warm up but are still quite damp. By mid summer, when we’ve dried out a bit and soil moisture is lower, they are mostly inactive, to only return when things get damp again in the fall.

S2S’s were made with folks on top of summits in Scotland, the western U.S., the Appalachians, France, Spain, and Germany. Bolstered by this success, but also not seeing many European activators spot themselves on SOTAWatch, I re-oriented my double to be 10 degrees east of North, which its direction of highest gain towards the Western U.S. (specifically the Pacific Northwest). I commenced calling CQ on 15m again, and was delighted to be rewarded with the familiar “Foxtrot 4 Whiskey Bravo Novembair” in dulcet French tones (does the activation even count if he is not in the log?), in addition to chasers from all over the U.S., including more New Hampshire and even a few Massachusetts stations (presumably line of site) and a nice chat with a chap in Northern Ireland. The bands seemed to shut down yet again, and the cloud ceiling had lifted a little, so I took a break and climbed the tower a second time, in addition to looking in more detail at the rock outcrops on the summit.

After a snack, I chased a few more activators, but at this point, it was dark in most of Europe or getting there: spots from European activators were drying up as they were packing up and heading home, and intense QSB was making QSOs with some German and Scandinavian(?) activators impossible: I could barely hear them and the band would fade out before we could complete the QSO. I was getting tired and hungry and a little grumpy. I took down the antenna and stowed my HF gear, in my pack, and rounded out the day with a single contact on 2m with a station 40 miles away near the Connecticut border using my trusty 5W handie-talkie.

All in all, 30 contacts in 2.5 hours, which isn’t the wild pace and numbers I’ve become spoiled by with Parks on the Air, but it will do for only putting 20W peak power into some cheap speaker wire. I was very pleased with a total of 17 summit to summit contacts, 9 of them being across the Atlantic with operators in Europe, true to the theme of the event. That, along with being outside in the woods for several hours on an early spring day, was very much a success.

The sky, by this point, was a clear, almost cloudless blue, and it was sunny and warmer, so I climbed the tower one last time to take in the views. On the hike out, I was annoyed by a guy on a very shiny, new, and expensive looking quad zooming through the wildlife sanctuary with his kid, who, given the geography of the area, had to be a local— it left me wondering if he was a resident of one of the new ridge-top $3/4 million, or more, trophy homes that have sprouted up with increasing frequency here in the past 4 years. The sanctuary is strictly off limits to wheeled and motorized vehicles, but I’ve yet to see it enforced: dirt-bikers from out of the area, folks like this, and D2R2 style gravel-cyclists and mountain bikers from the city violate this rule all the time. Putting it out of my head, with my stomach reminded me how ravenous I was, I got to my car and drove into town for some celebratory tacos, followed by a hot soapy shower and mandatory tick check.