A very jolly SOTA activation

December 7th, 2024

One of the things I most enjoy about Summits on the Air (SOTA) is the comraderie, especially on event weekends. Here I am, along with a a few dozen other nerds of a very specific flavor, making a (more often than not) solitary trek up a mountain with radio gear for the explicit purpose of contacting those other folks, while another few dozen nerds, again, of a very specific variety, cheer us on from home and wait for the moment they can contact us. It’s pretty neat!

It was in this spirit that I dragged myself out of bed early on a recent Saturday to participate in the SOTA W1 region association’s winter Summit-to-Summit weekend, wherein a bunch of folks all around New England would climb summits and all try to contact one another. Assuming we all woke up and got to the tops of the mountains at the same time, of course.

I was feeling low energy, and much of my part of New England was under several inches, if not almost a foot, of snow. I didn’t want to try anything too ambitious. In hindsight, I realized I should perhaps save the easy, short-hike or drive-up local SOTA summits as backup plans for late-in-the-year winter events like these instead of checking them off in nicer weather. Live and learn! I ended up picking Jolly Mountain in southern Vermont (W1/GM-207), as it’s a relatively short hike preceded by a relatively short drive from my house, and I was absolutely certain I’d have the summit to myself, as it’s not on public land (albeit, not posted at all and with tons of trails) and doesn’t have a view. I would be lying, too, if I didn’t admit that I picked it for its name given the time of the year. Ho ho ho!

The town-maintained dirt road to the general area was in excellent condition, with the plow making a nod to the fair-weather pulloff at the unofficial trailhead by making the road a smidgen wider there. I put on my hat, hoisted my pack out of the trunk and buckled the hip strap, made a few adjustments, and set off into the woods and about 8 inches of snow, sans snowshoes but with microspikes equipped. I’d never been well-trained in how to use snowshoes, and I find that in anything under a foot of completely unblemished snow they’re just as much, if not more, work and frustration than postholing, especially on steep and bumpy terrain like is expected near the summit of this hill.

The squeak and swish of the surprisingly light and fluffy snow broke the quiet as I made my slow way, with much fatigue, up the short trail through open hardwoods. For a brief distance I followed someone else’s tracks before they made a beeline into the brush. There were abundant fresh deer tracks as well, much to the delight, I imagine, of hunters during the last week of black powder season in Vermont. As I went further up the trail, snow was sticking to the boughs of increasingly dense hemlocks: both tall and old and short and young, making for a very magical and hush-quiet atmosphere, with animals making nary a peep. One of my favorite color palettes is the white-green-brown-grey-blue of a mixed New England forest on a clear day in winter: hemlocks and birch rising from the snowpack to an intense blue sky with wispy clouds, everything in crystal sharp focus and intense colors for the very limited palette. During the hike up, I swore I heard a single bleat from an American Woodcock, which would be most unusual for this time of year.

At the top of the mountain (a hill, really) I selected a small bump, about the size and height of a post-2016 American extended cab short-bed pickup truck (the kind you only see out here with NY/CT/NJ plates or Boston MetroWest transfer station stickers going about 80 mph on the 2 lane road to Okemo), of snow-covered bedrock as to give my antennas a completely unobstructed view in all directions. Jolly Mountain is similar to a lot of the taller hills on the Miocene-ish peneplain here in that it’s a short north-south, and very narrow, ridge on a broader, high elevation plateau, with one side being a very steep dropoff of 100+ feet or more. Locally, such hills have very high prominence, allowing them into the SOTA ranks. Being local heights of land without obstructions, they make absolutely fantastic operating positions for long-distance radio. This summit is wooded with no clear view, but is still quite lovely in the winter– the trees are spaced far enough apart that one gets a wonderful sense of the shape of the surrounding land, silhouettes of far off mountains and the suggestion of closer hills peaked between tree trunks, hinted at by the blue-grey haze of snow under the fuzz of the forest on the slope across the way. The main view in this regard is to the east, across the narrow Connecticut Valley and into the broad upland of southern New Hampshire and the Worcester plateau halfway between myself and the ocean, 100 miles distant; elevations the same as the landscape surrounding this summit with their own monadnocks being just as tall, or taller, than where I sit.

It took me quite a while to set things up. Being on top of moss-covered rock under tree canopy, I had to pile up and pack down snow to secure the ground spike of the cheap (yet highly effective) HF vertical telescopic whip antenna I brought, after selecting a location where it wouldn’t touch any tree branches. I followed advice from N7KOM for winter SOTA activations and brought a tarp to lay my gear on, in addition to sit. The tarp is just clear 6 mil plastic I had left over from a house project: it will do the job until I can find a large piece of Tyvek or purchase a piece of nylon cloth. It kept my gear clean, orderly, and relatively dry, but the drawback was that in the deep and fluffy snow the tarp sank when sat upon, drawing the edges (and snow!) into its center, in addition to being very, very, very slippery! I lost a few pieces of gear over the 10 foot high cliff that marked the edge of the micro-topographic bump I was on and had to climb down to retrieve them. I then set up a 2m slim-jim antenna by hanging it from an overhead tree branch to use with my 5W HT, which was much easier. In hindsight, I should have just done this first and gotten on the air ASAP, as VHF that morning was downright cracking…

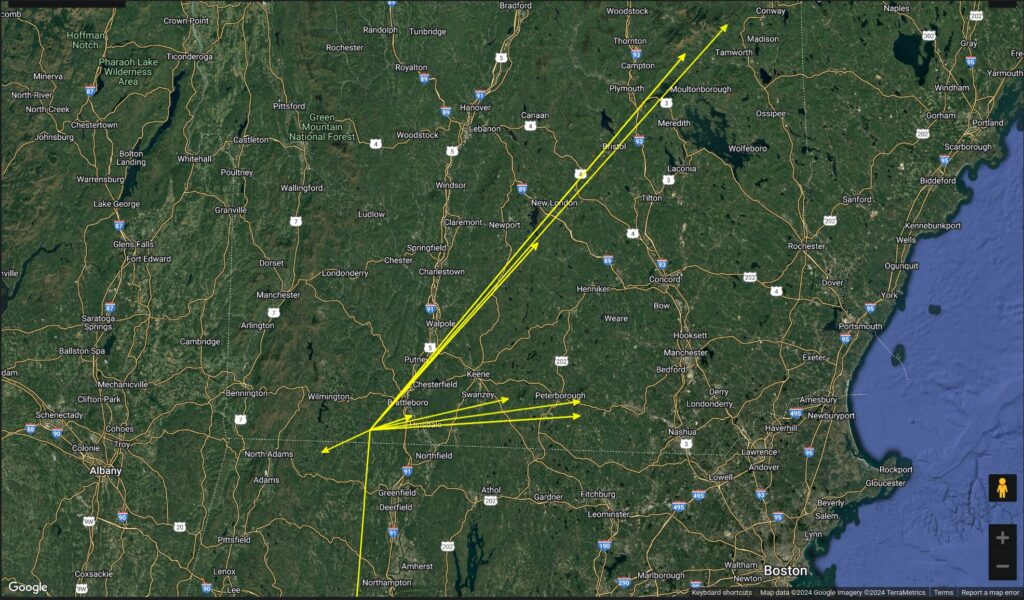

… Once settled in, and with an oatcake and cup of hot ginger tea in me, I checked SOTAWatch and saw a spot for a fellow W1 SOTA activator ~42 miles distant on top of Holt Peak on Temple Mountain in southern New Hampshire. I then, in short order, made several summit-to-summit, HT-to-HT, contacts on 2 meters with other hams participating in the event, almost all of them on New Hampshire summits. The real surprise came when I looked up the locations later at home: one contact was with a fellow activator on Mount Paugus in the White Mountains, ~107 miles distant, and the other with a Mastodon friend freezing themselves 97 miles away on Mount Israel (with a better view than mine)! I was also delighted to be chased by a SOTA couple on their hike up Mt. Sunapee to activate it for the event: I’d been unsuccessfully trying to get S2S’s with them for over a year; they technically weren’t in the activation zone of their summit yet, so this didn’t count. I even overheard a ham on mobile in the town of Dracut, 72 miles across the state of Massachusetts, telling another activator that he had heard me as well. Another delightful surprise was a nearby ham responding to my calls, who, coincidentally, had been my first ever QSO back in March 2023, during my first ever SOTA activation! He didn’t remember me, but I thanked him for his patience with me back then. A mobile station traveling up I-91 to Keene also kept me company and checked in several times with fun commentary and to ragchew a little bit between contacts when things were quiet. As they say: when it comes to VHF, height is might and this activation definitely proved that point! I also suspect that the slim-jim helped quite a bit with its higher gain in the horizontal-plane and low take off angle.

Writing about it a day later, I’m still in awe of what 5 watts and a clear line of sight can do. It felt like a party! Various folks monitoring VHF were popping in to say hello and ask what we were doing. It was a hoot, although I was sad to not hear many of the usual New England SOTA chasers that I normally get in the log. All in all, I made contact with 13 stations on VHF in about 45 minutes, which, for me, is a lot!

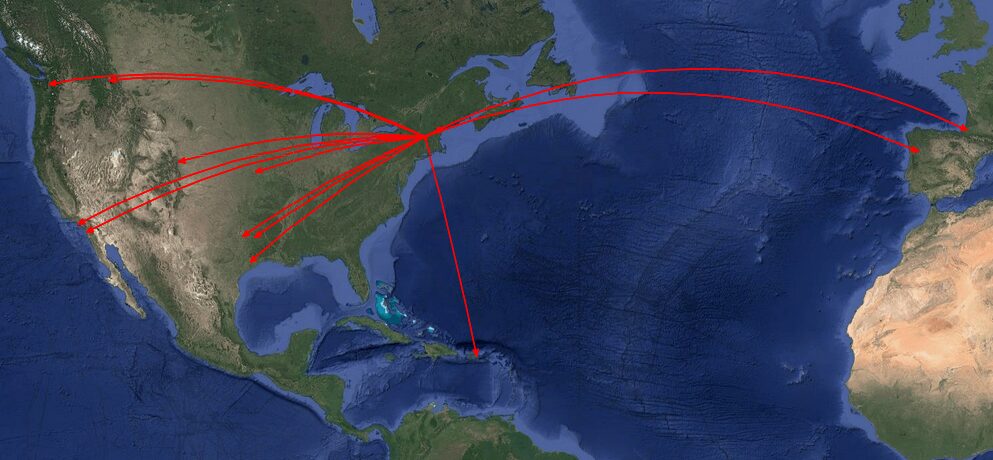

As I unpacked my HF rig (A Xiegu G90) and connected the antenna, the monkey-cries of a pileated woodpecker rippled through the bare woods, no doubt checking out what a strange creature had set up shop on top of their hill. The 10m band had been good as of late and I wanted to try my luck there with my new-ish 18′ telescopic whip I got for super-cheap from a certain international site that many hams use for such things. Within seconds of calling CQ, I heard from Christian F4WBN in France, making this activation Official! After that, snow showers began again, deepening the hush on top of the summit and collecting on my tarp and pack. It felt like slow going, but I heard from stations in Kansas, Washington State (Woohoo! In-country DX, as I call it), Montana, a ~15 mile line-of-sight contact in Vermont using a 100W mobile station on top of another mountain (LOUD!; not a SOTA S2S, sadly), California (Woohoo!), New Hampshire, Louisiana, Puerto Rico, and a summit-to-summit with an activator in Portugal! 14 contacts in ~20 minutes on 10m when all was done. I’m really impressed with what 20W and a compromised antenna can do! I credit the very low takeoff angle of the vertical on top of a mountain, and like to think that the snow might have made for an excellent ground plane. But the ionosphere calls the shots in the end.

I wanted to stay longer, but I don’t currently have appropriate winter boots for being out for long periods in the snow and had forgotten my gaiters. The temperature had warmed to just above freezing in the few hours I was on the summit, so the snowpack was wetter and clumps were falling off trees in the breeze onto me and my gear. My feet were soaked and I was starting to shiver in spite of my ample snacks, multiple dry and good wicking layers on the rest of my body, and thermos of hot ginger tea. Moisture management is critical in the winter, and in spite of my careful layer management, I had gotten just sweaty enough on the hike up that I had lost more heat than I liked in the few hours I was sitting on the summit. The slow snow flurries that were pleasant and atmospheric during most the activation were now coming down in earnest and a breeze had picked up. It was time to hike the 20 minutes back to the car, warm up my toes, and head home.

To be perfectly frank: I full well knew, setting out, that I was putting myself into a borderline dangerous situation given my lack of better gear (anyone want to buy me winter boots?) and physical state (anyone want to buy me better doctors?). While people knew where I was, I was close to a road and houses, I had check-in plans and multiple communications options (I loathe how paramilitary fetish / tacticool “opsec” that all sounds), and this wasn’t even a walk to the mailbox, as far western New England hikes are concerned; even with my 25+ years almost daily professional experience working outdoors and in wilderness year-round, this could have easily been a disasterous move on my part. Don’t be like me: proper footwear, clothing, moisture management, etc., is paramount, even acknowledging the access barriers that creates for most folks. I see a lot of arguably undeserved judgement and gatekeeping online (always online) towards people who get themselves into bad situations outdoors. Here in the northeast, a significant percentage of those people are like myself, with decades of outdoor experience and wilderness training, who, like humans everywhere, inevitably make a bad judgement call either from fatigue or a similar overconfidence that you see in the Monday morning quarterbacks using stories of these folks’ misfortune to make themselves feel important. Most of the U.S. population is prevented from having access to wilderness and that’s one issue, but for those of us who are experienced, whether it’s earned firsthand or voyeuristically, hubris and an overconfidence in our training and skills, can be just as deadly.

It was the most fun I’ve had playing radio in a while. It renewed my commitment to experiment more with weak signal, low power, and long-distance VHF and UHF. I also absolutely love being out in the quiet of the New England woods when there’s snow on the ground. It’s a spiritual experience at what is, to me, the apex of the Year– when the land is in a deep sleep and I’m walking in the stuff of its dreams, a more silent time out of time when there’s a different awareness watching you, a clear, austere, and crisp and yet quiet quality to being. The constant conversation with the landscape deeper, more intimate, more bare. The land is transformed: it’s a very different place than the lush visual cacophony of the summer (I say visual, because the woods in New England are still eerily absent of much bird and insect song even in the thick of summer, compared to elsewhere). I think to what it looked like as tundra a mere 12,000 years ago when the ancestors of the present day nations of the Nipmuc, Mohegan, Abenaki, and their kin were at the beginning of their millennia of history here, ice and unimaginably bitter cold to the north, a large lake down in Valley. After a vanishingly small 24 winters here, I understand why Bernd Heinrich wrote A Year in the Maine Woods and Winterworld; There’s nothing like it, and I wouldn’t give up the experience and its seasonal rituals lightly.